By: Andrés Aguirre, Luis Filipe Ponce and Sofia Ruiz de Teresa

Published: May 13, 2024 | Updated: July 17, 2024

Read time: 15 minutes

- Table of contents

Introduction

Six countries. Six progressions of open banking or, more broadly, open finance. A number set to increase as other countries follow.

Financial institutions, whether operating in one country or across many, now face the task of fathoming an entire region.

What untapped opportunity might exist in one country based on its evolution in another? What approaches can and cannot be replicated across different countries?

Brazil enjoys comprehensive regulation. Colombia’s initial focus is on payment initiation services (PIS), while Mexico’s fintech law only covers account information services (AIS) even as the central bank explores PIS. Chile also adopts a fintech law but specifically includes PIS. Argentina and Peru tease regulation in their approaches to real-time payments.

Their shared goal of stimulating competition and innovation is inherited from open banking’s regulatory foundations in Europe. They then add another goal: financial inclusion. Its urgency varies across the six.

Mexico’s banked share of 45% at one end contrasts with Chile’s 89% share at the other, according to Mastercard Market Trends analyses using data from RBR Data Services and the World Bank (henceforth MMT); the underbanked share runs higher across both. Such considerations underscore an emphasis across the countries on low-value digital payments to reduce dependency on cash.

Mexico’s banked share of 45% at one end contrasts with Chile’s 89% share at the other.

Less cash means more financial inclusion. The associated digital payments create opportunities for alternative credit scoring and further financial inclusion. Meanwhile, real-time payment rails, which thrive on open banking while also helping open banking to thrive, are becoming an expectation for digital payments.

The different flavors of open banking across Latin America warrant a two-pronged analysis of each of country:

- Regulations and infrastructure: A look behind-the scenes at top-down frameworks and technological capabilities.

- Market backdrop and opportunities: A look at consumer habits and roles for financial institutions.

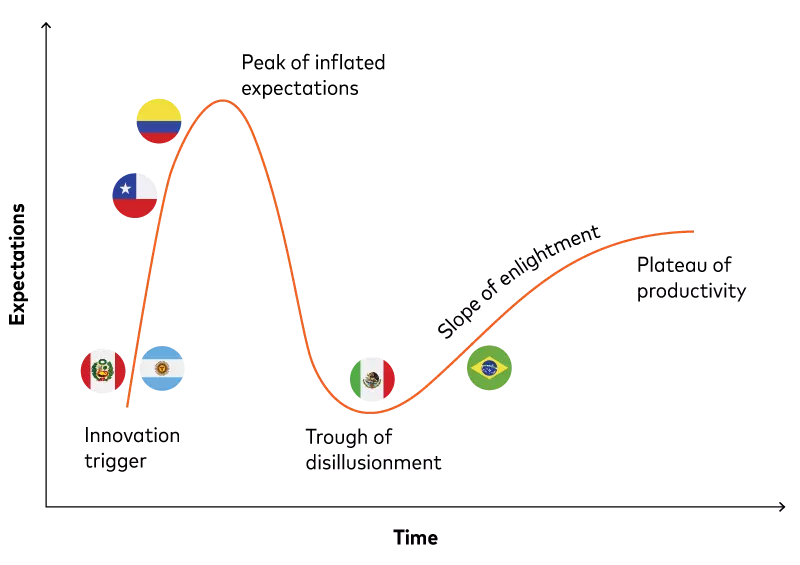

A crude plotting of the six countries on a “hype cycle,” a map used by the US consultancy Gartner to show the maturity and adoption of emerging trends such as open banking, produces the following:

Open banking’s hype cycle

Brazil’s leading position on the “slope of enlightenment” is significant for two reasons. First, it is the only country to be solidly demonstrating the clout of open banking in the region. Second, its achievement eclipses Mexico’s status as the first mover and reshuffles the chronological order used below, which is based on when each country entered the cycle.

- Explore more

Four European takes on open banking

Purposeful & profitable: Financial inclusion via open banking around the world

Open banking in Mexico

Part 1: Regulations and infrastructure

In some ways, Mexico is a pioneer.

In 2018, Mexico was one of the first countries globally to introduce regulation for open banking, not to mention its broader focus on open finance. That was the same year the EU’s revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2) came into force and promoted secure application programming interfaces (APIs) over web scraping for data sharing.

In 2019, Cobro Digital (CoDi) brought low-value retail transactions to Mexico’s Sistema de Pagos Electrónicos Instantáneos (SPEI) real-time payment infrastructure. The launch of Brazil’s comparable Pix payment scheme was still a year away.

Mexico’s entire approach was also innovative.

First, it couches its open finance regulation within a “Fintech Law”. The novel inclusion of fintech companies as providers, not just recipients, in a two-way flow of data befits the country’s status, alongside Brazil, as one of Latin America’s two fintech hubs. And the option, even if not acted upon, to charge non-prohibitive fees for data access recognizes growing parity between incumbents and fintech startups.

Second, the law puts financial inclusion on a par with promoting competition in its list of motives. By comparison, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority views financial inclusion as one of open banking’s “new developments” that was not an original consideration.

Yet, the path of a pioneer is often the most challenging.

Mexico’s lack of full API standardization is not unusual worldwide, nor is its inclusion in its fintech law of account information services (AIS) without payment initiation services (PIS). But both pose challenges.

While a data aggregator can help even when connecting standardized APIs, it is largely essential when going beyond one-to-one private connections. Multiple private aggregators operating around different standards mean open banking in Mexico lacks ease and cohesion and often still resorts to web scraping. And despite its pretensions of open finance, it also lacks scope because no PIS regulation yet exists to accompany the first set of secondary provisions for AIS from 2020 despite interest in PIS from the central bank.

For now, SPEI in Mexico cannot benefit from open banking like Pix can in Brazil. The situation does not in itself account for the lackluster uptake of CoDi so far, but it does not bode well. Only 1.6 million accounts in a population of nearly 128 million made at least one payment with CoDi in the four years since its October 2019 launch, according to central bank data.

For now, SPEI in Mexico cannot benefit from open banking like Pix can in Brazil.

The launch of Dinero Móvil (DiMo) in September 2023 aims to boost uptake by linking phone numbers to accounts along the lines of Pix. Its impact remains to be seen — in particular, whether it has any bearing on the private “closed loop” alternatives to CoDi set up by fintech companies not directly linked to SPEI.

Part 2: Market backdrop and opportunities

On the one hand, financial institutions in Mexico are for now somewhat stymied in three areas: limited API standardization, absence of PIS regulation, and poor uptake of low-value real-time retail payments.

In addition, only 45% of Mexico’s adult population has a financial account — the lowest percentage against a six-country average of 70%, according to MMT. A more liberal interpretation, which includes pre-funded mobile money accounts with electronic money institutions, still only pulls the share up to 49%, according to the World Bank’s global financial inclusion database (Findex). And mobile phone penetration at 80% is the lowest among the six countries against an average of 89%, according to the Findex.

Mexico’s 773 fintech companies at the end of 2023 amount to the second highest in the region after Brazil.

On the other hand, Mexico is home to Latin America’s second-largest economy and population after Brazil. Its 773 fintech companies at the end of 2023, according to venture capital firm Finnovista, amount to the second highest in the region after Brazil. Private API aggregators work around the lack of standardization, a PIS framework is inevitable, and real-time payments are already available.

Many financial institutions already work as or with account information service providers (AISPs) in areas such as financial management and lending. Highly banked customers are obvious starting points, but alternative credit scoring with inputs from mobile money accounts may expand reach to unbanked and underbanked customers. Remote account opening and onboarding with e-KYC (know your customer) can also access hitherto hard-to-reach groups.

Credit scoring platforms can even provide scores to affiliated lenders so they can compete for consumers who can then avoid the “poverty premiums” associated with limited loan options. And a lack of PIS for now does not restrict payment services, which may include buy now pay later (BNPL) for mobile money accounts with credit limits tied to responsible use.

Mexico is stalled in open banking’s “trough of disillusionment” for now, but it will inevitably rise out. The opportunities for financial institutions might not currently be as diverse and abundant as they are in Brazil, but they also have not yet been exploited by competitors.

Open banking in Brazil

Part 1: Regulations and infrastructure

If Mexico is the pioneer, then Brazil is the benchmark.

A little over two years after Mexico in 2018, Brazil released its regulation on open banking in 2020. There are similarities: fintech startups and incumbent banks are on a level playing field, and the scope includes open finance data. Yet Brazil’s approach has a different twist.

Instead of incorporating open banking into a fintech law that anticipated further specific regulation, Brazil went specific and comprehensive at the outset. Phase 1 of the regulation went live in early 2021 followed by an AIS-focused phase 2 and a PIS-focused phase 3. As Mexico stalls, Brazil is in its fourth “open finance” phase, which goes beyond banking to open insurance and open investments.

In June 2023, Brazil’s 4.8 billion successful API calls more than quadrupled the UK’s 1.1 billion.

On 1 February 2023, exactly two years after the launch of phase 1, Brazil’s central bank was celebrating 15 million users, according to the central bank. In June 2023, Brazil’s 4.8 billion successful API calls more than quadrupled the UK’s 1.1 billion, according to a Mastercard analysis based on stats from the Banco Central do Brasil and UK Open Banking Limited. Granted, Brazil’s population is over three times larger, but Brazil also took three years less than the UK to achieve the feat.

Open banking in Brazil now also syncs with Brazil’s Pix real-time retail payment system. Pix was launched in November 2020 and reached 140 million users in two years. As of October 2023, usage is at 156 million or over 70% of the population.

Part 2: Market backdrop and opportunities

A comprehensive approach to open banking synced with a popular real-time payments system makes Brazil a prime market for innovation.

The share of credit transfers in Brazil as a percentage of cashless transactions is at 42% according to MMT. The percentage is second highest against a six-country average of 37%, which is already skewed upward by Peru’s outright dominance at 81% under different market conditions.

Brazil has also stamped its supremacy on the fintech scene after vying for years with Mexico as Latin America’s fintech hub: Brazil’s 771 fintech companies in 2021 compares with 512 in Mexico, according to Finnovista. Mexico reached a comparable 773 by the end of 2023.

Yet unlike in Mexico, first-mover advantage is increasingly unavailable as Brazil progresses along the “slope of enlightenment.” Alternative credit scoring, instant and largely automated onboarding, and personal financial management (PFM) with consolidated views across other providers’ accounts are increasingly givens.

The space has already evolved into additional services, such as cross-selling services based on financial need or PFM tools alerting customers when any account, including ones from other providers, risks becoming overdrawn. Throw in PIS, and providers can offer automated investments such as the use of variable recurring payments with sweep accounts in the UK.

An emerging opportunity exists where Pix and PIS come together at the embedded finance interface of open banking and Banking as a Service (BaaS). The centralized nature of Pix means a consumer can make a payment without leaving a retailer’s site.

Open banking in Colombia

Part 1: Regulations and infrastructure

In May 2023, the fintech industry bodies spanning the Pacific Alliance countries — FinTech México, Colombia Fintech, FinTech Perú and FinteChile — came together to discuss open finance standards.

Colombia’s 2022 open finance decree focuses on PIS. Mexico’s 2018 fintech law focuses on AIS.

The collaboration is timely. A common approach contrasts with an almost inverted relationship between Colombia’s and Mexico’s approaches: Colombia’s 2022 open finance decree focuses on PIS; Mexico’s 2018 fintech law focuses on AIS.

Colombia’s plan to introduce AIS in 2025 as phase 3 of its four-phase approach, followed by financial portability in phase 4 in 2026 to facilitate transfers of all customer information associated with financial products, will bring alignment in one direction while leaving PIS as a differentiator in Colombia for now. Meanwhile, Colombia’s successful completion in February 2024 of a “general” phase 1 keeps it on track for releasing specific PIS standards by December 2024 as phase 2. But for that, Colombia also needs specificity in another area: real-time payments.

Colombia currently offers three schemes that support low-value account-to-account payments: Botón PSE (Pagos Seguros en Línea), Transfiya and Redeban Entre-Cuentas. Unlike Mexico’s CoDi/DiMo and Brazil’s Pix, they are all run privately rather than by the central bank. ACH Colombia, an automated clearing house owned by a consortium of banks, runs the first two; Redeban, a payment service provider, runs the third.

Botón PSE is the oldest and most established of the three: it is accepted by over 23,000 retailers and over 30 financial institutions; half of Colombians in a recent survey by the Mastercard Account-based Payments Advisory (APA) claim to use it. Yet it is only “real time” from a user perspective since participating banks settle funds after the fact via ACH rails. It competes with other digital wallets from individual banks or electronic money institutions that, unlike Botón PSE, tend to support QR codes.

Transfiya and Redeban Entre-Cuentas are both real-time networks. Transfiya began in 2019 with peer-to-peer (P2P) transfers but is now dallying with peer-to-merchant (P2M) along the lines of its PSE counterpart. Redeban Entre-Cuentas focuses since late 2022 on interoperable QR codes across Colombia’s digital wallet providers and then handles the transactions on its real-time rails.

In October 2023, the central bank stepped in with regulation to resolve confusion by stipulating the interoperability of all low-value real-time payment systems. The goal is a Sistema de Pagos Inmediatos (SPI) — an acronym shared with Brazil’s Sistema de Pagamentos Instantâneos (SPI), which is branded for users as Pix — with a centralized directory and centralized settlement. SPI’s success will hinge on compatibility between Transfiya and Redeban Entre-Cuentas along with an iconic popularity to match Botón PSE.

Part 2: Market backdrop and opportunities

Cash withdrawals represent 61% of payment card gross dollar volume (GDV) in Colombia, versus 46% in Mexico and 24% in Brazil. Across the six countries, only Peru is higher at 66%. Meanwhile, Colombia’s 32 card payments per year per adult ranks the lowest of the six countries with under half of Mexico’s 65 and far below the leader Brazil’s 238, according to MMT.

Colombia’s 62% penetration of contactless cards outperforms Brazil at 35% and Mexico at 22%.

But within that cash dominance lie a couple of anomalies. Banking levels in Colombia at 65% are higher than Mexico at 45%, albeit still less than Brazil at 85%, and a 62% penetration of contactless cards outperforms Brazil at 35% and Mexico at 22%.

The banking levels are boosted by agency banking, where local retailers operate as banking agents who deliver financial services on behalf of banks, in what may be considered a forerunner of Banking as a Service (BaaS). The use of contactless debit cards on Bogotá’s public transport system likely accounts for high contactless penetration despite relatively limited card use otherwise.

What results is a population well-served by bank accounts and willing to go cashless if convenient. The scenario is unfolding in a country on the brink of benefitting from ample regulation and supporting infrastructure.

Private API aggregators take care of the lack of API standards for now and support AIS staples such as PFM and alternative credit scoring. Meanwhile the Colombian push for PIS means financial institutions are already initiating payments on behalf of consumers.

As Colombia reaches the “peak of inflated expectations” on the hype cycle, financial institutions have the chance to keep the ensuing trough as shallow as possible.

Open banking in Chile

Part 1: Regulations and infrastructure

The natural point of comparison for Chile’s 2023 “Fintech Law,” whose supporting regulation is expected in the middle of 2024, is Mexico’s fintech law from almost five years earlier in 2018.

Mexico has the infrastructure but has not yet enabled PIS. Chile does not restrict PIS, but its Transferencias Electrónicas de Fondos do not support low-value retail payments.

Yet unlike the single “artículo 76” in Mexico’s law, Chile’s law dedicates an entire “título” with multiple articles to its Sistema de Finanzas Abiertas (SFA) for open finance. Specific API-based regulations tied to standards for AISPs and PISPs are expected in late 2024. For now, financial institutions self-regulate web scraping when conducting open banking.

Real-time payments introduce another difference. Mexico has the infrastructure but has not yet enabled PIS; Chile does not restrict PIS, but its Transferencias Electrónicas de Fondos (TEF) from 2008 do not support low-value retail payments.

Chile is now exploring the opportunity to sync low-value real-time payments with open banking from the get-go. In that sense its situation is more comparable to Colombia, which sits at a similar position on the hype cycle, than Mexico.

Part 2: Market backdrop and opportunities

The lack of anything comparable in Chile to Colombia’s Botón PSE makes sense in an economy where cash does not dominate.

At 23%, Chile has the lowest share across the six countries of cash withdrawals as a percentage of payment card GDV, according to MMT. That share is far lower than Colombia at 61% and even squeezes in below Brazil at 24%. Yet unlike Brazil, Chile has not hoovered up many of its former cash users with a real-time payment solution like Pix.

Chile’s banking levels of 89% are the highest against a six-country average of 70%, and the number of card payments per adult per year stands at 235 against a six-country average of 117 and just shy of Brazil at 238, according to MMT. At 89%, Chile also has the highest smartphone penetration against a 75% six-country average.

As home to 300 fintech companies, according to Finnovista, Chile is no fintech slouch either. Still, its total remains under half that of the leaders Brazil and Mexico, and lags Colombia and Argentina with 369 and 343 apiece.

Chile’s high banking levels make financial inclusion less of a priority and may give open banking services a somewhat European bent.

Pending API standards do not prevent financial institutions from operating as AISPs and PISPs. However, high banking levels make financial inclusion less of a priority and may give open banking services a somewhat European bent, such as the AIS-based bill aggregation services offered by most major Chilean banks. Connecting bill aggregation to bill payments is a natural next step already offered by some PISPs.

Perhaps less expected in Chile’s highly banked and carded market is the demand for in-store account-to-account payments. Although there are no plans yet for a dedicated standalone low-value real-time payments infrastructure, the central bank is supporting the development of low-value clearing houses for retail payments.

An explanation comes from a comparison with a country such as the UK, where financial inclusion is viewed as one of open banking’s “new developments” rather than an original objective. Chile’s 23% share of cash withdrawals as a percentage of card GDV compares with 9% in the UK, according to MMT country reports. And its 89% banked population compares with near universal access to banking in the UK.

Even more telling are relative card ownership levels for people 15 years and over: 24% credit and 79% debit in Chile versus 62% and 95% in the UK, according to the Findex. Lower levels in Chile relative to the UK further correlate with higher levels of mobile phone use for payments. In Chile, 41% made a digital in-store retail payment using a phone in 2021; the UK share was 26%. Similarly, 45% made a utility payment using a mobile phone in Chile versus 14% in the UK, according to the Findex.

As Chilean financial institutions monitor European approaches to increased financial inclusion, they will do well to keep it simultaneously couched within Latin American approaches closer to home.

Open banking in Argentina

Part 1: Regulations and infrastructure

Argentina and Chile share one of the world’s longest international borders. Their approaches to open banking and real-time payments are for now perpendicular. Where Chile has released open banking regulation with an eye on real-time payments, Argentina’s focus on real-time payments is teasing open banking.

The central bank’s Transferencias 3.0 went fully live in 2021 to provide interoperable QR codes for real-time account-to-account payments. To better support funding mechanisms for digital wallets, the central bank is also replacing its “débito inmediato” (DEBIN) real-time debits with “transferencias inmediatas ‘pull’” (TIP) to give consumers more control.

Chile has released open banking regulation with an eye on real-time payments, while Argentina’s focus on real-time payments is teasing open banking.

Yet a lack of centralized branding, such as the logos for Brazil’s Pix or Mexico’s DiMo, has left a consortium of almost 40 financial institutions to shore up Transferencias 3.0 via a self-proclaimed “wallet of banks” known as MODO.

The relationship between MODO and Argentina’s largest digital wallet, an extension of the country’s largest e-commerce platform, continues to play out. The central bank is pushing rapprochement through a May 2022 communiqué stipulating that all digital wallet providers must allow consumers to link any bank account even if not one offered by the wallet provider itself.

The central bank’s communiqué is about linking accounts rather than securely sharing account data, so it is not open banking per se. But its open approach is in the spirit of open banking and exists as an “innovation trigger” on the hype cycle as a likely harbinger of regulation.

Part 2: Market backdrop and opportunities

Interoperable QR codes should appeal in Argentina where smartphone usage is at 81% and mobile phone usage is nearly ubiquitous at 92%, according to MMT. Of the six countries, only Chile bests those percentages with 89% and 96%.

Transferencias 3.0 helped payments though mobile devices in April 2023 reach 198.8 million, according to the central bank. Still, the 198.8 million transactions represent under two-thirds of the 308.7 million transactions made exclusively across debit and credit cards that same month. The figure also somewhat misleadingly seems to include payments made with cards stored in digital wallets on mobile devices.

So, despite continued growth in account-to-account payments, Argentina’s share of credit transfers at 19% of cashless transactions is the lowest across the six countries against an average of 37%, according to MMT. From that perspective, Argentina and Chile’s perpendicular approaches occur in similar contexts after all: relatively high banking levels and limited use of credit transfers. The difference comes from Argentina’s cash dependence and an initial focus on payment initiation more along the lines of Colombia.

Argentina’s dominant digital wallet provider cannot offer all the convenience at home that it offers in Brazil as a PISP.

One current Argentinian particularity is how market volatility makes PFM and real-time payment initiation into valuable tools for individuals and businesses wanting to avoid being caught out by currency fluctuations. The desire is palpable: Argentinian comfort with cryptocurrency, hardly known for its stability, is highest out of the six countries: 28% of Argentinians claimed to have used it versus 16%–18% across the other five countries, according to a Mastercard study in early 2022.

For now, it is ironic that the country’s dominant digital wallet provider, used by 88% of Argentinians responding to a recent APA survey, cannot offer all the convenience at home that it offers abroad in Brazil as a PISP. Chilean-style web scraping and Colombian-style API aggregation are both prominent in the absence of formal open banking regulation.

Open banking in Peru

Part 1: Regulations and infrastructure

Chile’s fintech law now leaves Peru as the only Pacific Alliance country not to have an open banking or open finance regulation. A March 2022 bill declares open finance a “national interest,” but no regulation has yet materialized.

At present, Peru’s focus on real-time payments means its approach has in some ways more in common with Argentina than any of its Pacific Alliance counterparts.

Similar to Argentina’s 2022 communiqué, Peru’s 2022 circular may be seen as an “innovation trigger” for open banking.

Peru’s Cámara de Compensación Electrónica (CCE) automated clearing house has offered real-time payments since 2016, but it only moved to full scale and volume for its “transferencias interbancarias inmediatas” in 2022 with support from Mastercard. The involvement of Peru’s automated clearing house does however differ from the involvement of Argentina’s central bank. Although the CCE was established by Peru’s central bank in partnership with other banks, it is not part of the central bank.

Similar to how Argentina’s May 2022 communiqué may be seen as an “innovation trigger” for open banking, an October 2022 circular from Peru’s central bank has similar stipulations: all mobile payments and mobile wallets should be interoperable regardless of provider or account.

The 2022 circular aligns Peru’s dominant digital wallet providers, but it does not mandate use of CCE rails instead of pre-funded mobile money transfers. Nor are CCE rails needed for push payments over card rails using virtual debit cards, which are also used for near “real time” transfers by Peruvian providers.

The theory, according to a CCE statement, is that all providers will be incentivized to use the new rails. For now, no dedicated logo exists to distinguish CCE’s low-value customer-facing “transferencias interbancarias inmediatas” from all other “transferencias interbancarias.” It remains to be seen whether that will fall to a banking consortium like MODO in Argentina.

Part 2: Market backdrop and opportunities

The impact of the revamped CCE has been swift. Cash’s 81% share of transactions in 2018 dropped to 58% in 2022 as the share of real-time payments grew from 3% to 18%, according to a Mastercard study.

Add in pre-funded mobile money transfers, and the share of credit transfers in Peru across cashless transactions is highest across the six countries at 81%, according to MMT. At the same time, card payments are the lowest across the six countries at 18%. The situation is essentially the inverse of Argentina at 19% and 72%.

The comparison is however somewhat misleading. Card payments per adult per year in Peru are only 35 versus 102 in Argentina, which puts the countries on different foundations. Unsurprisingly, cash withdrawals as a percentage of card GDV are higher in Peru at 66% than in Argentina at 41% and are also the highest across the six countries, according to MMT.

Yet despite having the second lowest levels after Colombia of card penetration and use, 2.3 per adult with 35 total payments per year, Peru vies with Chile for the top contactless card spots. Peru’s 87% contactless-enabled cards and 44% contactless spending when using cards are on par with Chile’s 85% and 49%, according to MMT.

The 78% of Peruvians claiming to make online payments in a typical month represent almost as big a share as the 80% of Brazilians claiming the same.

The openness to contactless technology coincides with the rapidly growing use of mobile devices for payments. Despite no Pix in Peru, the 78% of Peruvians claiming to make online payments in a typical month represent almost as big a share as the 80% of Brazilians claiming the same across an APA survey of ten countries in central and south America. The 71% share of Argentinians falls below the 73% average.

Peru even just pips Brazil in the same APA survey regarding interest in a hypothetical “pay by account” app that lets users check account balances across providers before choosing an account for payment at any card-accepting retailer. The 85% share of Peruvian interest is higher than the 82% share of Brazilians and far higher than 73% share of Argentinians in the bottom spot.

Peru’s position at the “innovation trigger” phase of the hype cycle provides financial institutions with opportunities to innovate in anticipation of open banking in an emerging space as Peruvians increasingly transact digitally. That differs from opportunities in somewhere like Brazil, in the “slope of enlightenment” phase, to innovate with open banking in an already crowded space.

Conclusion: Context and consent

The use of an open banking hype cycle to represent the relative positions of Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Argentina and Peru is at best a crude approximation.

Take just regulations: targeted specificness can be supportive or constraining; nonspecific futureproofing can be frustrating or enabling. Few regulations sit solely at either extreme.

At the same time, new infrastructure and technology can pull an ecosystem together or add more clutter for the market to resolve. How much should be mandated from the top? How should financial institutions adjust their approaches accordingly?

Peaks and troughs on the hype cycle may be abrupt and short or gradual and protracted. Their gradients and lengths may vary not solely on country-specific considerations but also on individual product categories and customer groups within countries.

Europe is a case in point: open banking comes in a variety of flavors there too despite ostensibly similar operating circumstances across the region. Yet more pronounced flavors across Latin American countries do not make them any less blurred at the edges than their European counterparts.

The unifying concern for financial inclusion in Latin America is tied up with another issue: customer control and consent. It matters worldwide since the ability to securely handle and analyze customer-permissioned data is core to open banking. But additional challenges come when customers are unfamiliar with the financial system or do not trust it. Even Brazil’s banking levels of 85% struggle to allay concerns around fraud: estimated losses reached US$500 million in 2022, 70% of it attributed to Pix by the World Bank.

“Concerned that my information would not be safe” is the top concern with open banking for customers in Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Argentina and Peru, according to a 2023 Mastercard APA survey across central and south America. “I prefer to keep my financial information confidential” is second except in Peru where it narrowly slips into third. It is pipped by “Too difficult for me to organize and provide all of my financial information” — ironically a perfect opportunity for a PFM app using open banking.

Without customer permission, supportive regulations and infrastructure combined with promising market backdrops and opportunities will not matter. A good way for financial institutions to secure permission is by building and then maintaining customer trust. The application of existing privacy and data protection controls is integral to the delivery of open banking. So too is customer control of their data and transparency over how their data is used, which in turn pertain to broader issues of financial literacy.

If financial institutions are to succeed with open banking in Latin America, they will first need to change the curriculum. In so doing, they might also provide a lesson for the rest of the world.

Learn how Mastercard’s open banking solutions empower partners, build customer trust and foster financial inclusion in Latin America and worldwide with strategic guidance, technological deployment, in-market engagement and ongoing refinement.